Feature: Pucker Gallery (BOSTON, MA, USA)

Posted: May 9, 2012 Filed under: Art, Interviews, Travel | Tags: America, art, Boston, Brother Thomas, ceramics, charity, Gallery, pottery, Pucker 2 CommentsFOREWORD: When visiting Boston, MA, last month, I was completely enthralled by its thriving arts scene. There were art galleries and museums and theatres and street musicians everywhere.

One of the most exciting places I found was Newbury Street. It has everything you want from high end boutiques to Japanese supermarkets, but it’s their (sometimes inconspicuous) art galleries that really fascinated me. And so I decided to embarked on a quest to visit and put together a complete guide to incorporate every single one of them.

While that is still a work in progress (I’ve been to all 28 of them, but please bear with me as I write them up), I would in the meantime like to feature one gallery that made a particularly strong impression on me. The interesting thing about art galleries – or any place, for that matter – is that you can tell a lot about them just by the people who greet you. Overall, the gallery directors and staff I met are mostly lovely people, but Mr. Bernard ‘Bernie’ Pucker stood out especially.

I was both astounded by his seemingly infinite knowledge of art, and touched by his sincerity. He spoke gently but passionately. He is a man infatuated with art, and in love with life. And he wore a bow-tie.

Pucker Gallery will of course still be included in my upcoming guide. However, as I do not wish for its story to be limited by space in the guide, I decided to make this a featured article instead. I would like to express my thanks to Bernie and his gallery staff (Allison McHenry in particular) for their time and patience in showing me around and talking me through each piece of work with such tender loving care.

* ** *** ** *

PUCKER GALLERY

ADDRESS: 171 Newbury St, Boston, MA, 02116

WEBSITE: www.puckergallery.com

Mr. Bernard ‘Bernie’ Pucker. Photo from puckergallery.com.

‘When I first opened the gallery – it used to be called Pucker Safrai – in the basement space here back in 1967, there were no shops below street level,’ Bernie Pucker told me with a gentle, reminiscent smile. ‘The whole street was mostly residential. Nothing like what you see now.’

In order to attract visitors, he created an outdoor courtyard at the bottom of the stairs with a little help from an architect friend. The result resembles a mini peace garden in the urban landscape, complete with a working fountain.

‘We hoped that the sound of running water would attract people to look down to see where it is coming from.’

Bernie eventually bought the whole building in 1979, and the magnificent but unassuming five-storey gallery we see today was complete. During its first 20 years of business the gallery mostly showcased and sold traditional art pieces, such as works by Picasso and Matisse. But then Bernie was introduced to renowned Canadian-born ceramics artist Brother Thomas (Thomas Bezanson) one regular day in 1983, which ended up changing his outlook and interests entirely.

‘A customer needed to borrow our toilet,’ Bernie chuckled at the memory. ‘We got talking and then he started telling me about a great ceramics artist he knew, and asked if I wanted to meet him.’

Brother Thomas was the kind of artist who would create 1,200 pieces of work and then smash 1,100 of them because they were good, but not good enough. He became an influential teacher and close friend to Bernie, and introduced him to the beauty of pottery. The two corresponded by fax everyday for the next 23 years until Brother Thomas passed away in 2007.

Brother Thomas wrote beautifully, Bernie told me. ‘There would be lines of poetry embedded in his writings. They were simple, but powerful.’

These lines, along with photographs of his works, were published in a beautiful, non- year specific diary planner Bernie named ‘Celebrate the Days’ in 2000.

Over the years, Pucker Gallery has sold over 1,600 of Brother Thomas’s breathtakingly exquisite pots and vases. They now have about two-thirds of the artist’s legacy in their stock, and holds an exhibition displaying a selection of them every two years.

Those aside, the gallery also deals in a wide range of art in other media, including powerful oil paintings by artist and Holocaust survivor Samuel Bak, Roger Bowman‘s watercolour and gouache works, as well as authentic South African beer pots Bernie discovered in his travels to the country.

Most recently, Paul Caponigro‘s unique black-and-white photographs were added to their already huge collection. Bernie had initially been reluctant to display any photographic works, but was so captivated by the surreal and almost painting-like quality of Caponigro’s pictures that he now not only sells them, but bought some for himself, too.

Outside of art-selling, Bernie and his wife Sue started a charity project in 2008 called ‘Save the World.’ As a part of this ambitiously-named venture, they would hold evening events at the gallery and invite the CEOs of nonprofit organisations dedicated to helping children in America to attend. The gallery provides a ‘spiritual space’ (as Bernie likes to call it) for them to meet and hopefully come up with ways to make a difference to the lives of people less fortunate than us.

‘Nobody really needs art when there are wars and hunger out there,’ Bernie admits. ‘But art energises and enriches people’s lives, and we should do our part and give what we can.’

It is incredible to experience how much effort Bernie and his team must have put into creating such a soothing atmosphere at Pucker Gallery. There is a sense of calm there that is hard to find in the modern world, especially in such a bustling city as Boston.

The gallery captures the essence of what art embodies, and it is one of the most inspirational places I have ever been to. Oscar Wilde famously wrote in the Preface to Dorian Gray that ‘All art is quite useless,’ but Bernie Pucker has, with clear visions and hard work, fairly and squarely proved him wrong.

Watch this space for my upcoming Complete Guide of all the Newbury St. Art Galleries!

Greg Balla, Actor in ‘Blue Man Group’ (BOSTON, MA)

Posted: April 20, 2012 Filed under: Comedy, Interviews, Music, Stage, Travel | Tags: Blue Man Group, Boston, comedy, Greg Balla, theatre Leave a comment‘I’d be lying if I say I never get bored. It’s still a job,’ Greg Balla says. But then he leans forward and breaks into a sunny smile. ‘Though as far as jobs go, it really doesn’t get any better than this!’

Greg is one of those lucky people who found employment almost immediately after he graduated from New York’s Fordham University in 2008. He started off as an electrician, but now gets paid to be painted blue, drum on pipelines, and regurgitate marshmallow sculptures from the depths of his mouth onstage every night.

‘The best thing is that once the latex skull cap and blue face paint is on, I just become a Blue Man who has no ego and sees the world for what it is. This chair isn’t a chair to a Blue Man,’ he says as he strokes the seat of the bar chair next to him. ‘It’s a sheet of smooth, leathery material with bits of wood structured around it.’

‘Being a Blue Man is really liberating. It removes my identity and frees me from the constraints of being Greg Balla. When I first started doing this I was really conscious of the face paint. It’s greasy and sticky and smells like lipstick!’ he continues. ‘But now I’ve gotten used to it and don’t even notice it anymore. It’s become my second skin.’

As he spoke, I was struck by the passion with which he describes everything. His words are accompanied by a lot of hand gestures and an excited glint in his eyes. He smiles a lot, and occasionally pauses to apologise for ranting too much. There is something almost childish in the way that he bounces on his seat slightly, as though his enthusiasm just cannot be contained.

And then it hit me. Although the man sitting in front of me is not blue, bald or mute, Greg is still a Blue Man through and through. Not only has he fully come to terms with what his character is about, he has even aligned himself with it.

"Blue are the people here that walk around,

Blue like my corvette, it's standing outside.

Blue are the words I say and what I think.

Blue are the feelings that live inside me."

- Eiffel 65, 'Blue (Da Ba De)'

Photo by Gwen Pew, Apr 12.

‘Being a Blue Man has changed the way I look at the world,’ he says with a sort of wisdom that only a child can understand. ‘I’m now hyper-aware of everything and have a better appreciation for things we don’t normally see.’

‘As kids we’re free, but as we grow up we adopt all these social masks in order to fit in. The point of the show is to encourage them to unmask themselves.’

The Blue Man Group, as I mentioned in my review, manages to create a level of interaction with the audience that is rarely seen onstage. The fourth wall is completely shattered as the actors clambered over the ponchoed crowd and peered deep into our eyes (and, in some cases, handbags).

‘We try to connect with the people, which means that we have to be very sensitive to them and figure out what kind of show they want,’ Greg says. ‘There’s a template to the show and we have the dots – A, B, C, D – but the audience has to help us join those dots. Sometimes we get a tamer lot, perhaps because it’s the Sunday morning performance, while other times the people just want to party. We try to accommodate that.’

In order for the actors to fully focus on the audience, the actual mechanics of the show itself have got to be solid. Although a magician never reveals his tricks, Greg was more than happy to share the stage secrets when he kindly offered to give me a backstage tour.

I was amazed by how cleverly it all works. From the tubs of blue face paint lined up on the wall ready to be splashed on, to the tubes used to connect bottles of paint to the drum sets, to the colour-coded pipe-drums (each colour represents a different note), everything is meticulously planned out.

I also noticed that there was a certain sense of pride and familiarity in the way that Greg showed me round the labyrinth of corridors and rooms. He talked me through each prop and process as though the place were his home, and introduced me to everyone we walked past like they were family.

And that is what sums up the true spirit behind the Blue Man Group. It is their understanding of how humans connect with each other on a primal level that makes them so enchanting to watch onstage. The Blue Men may not communicate with spoken words, but as Greg puts it, they have a very basic yet powerful language that is able to transcend social boundaries and bring everyone together.

‘We just want everyone to have fun,’ says Greg with his signature grin. ‘The best thing is when you get a Dad there with his kids, and the kids are having a great time while he’s just sitting there looking stern and being Dad. But then at the end of the show when the toilet paper starts shooting out and the giant balls come down, I’d look at him again and see that he’s completely changed. He’d be laughing and joining in and loving it!’

‘That’s what we’re trying to achieve. That’s what we’re all about.’

* ** *** ** *

The Blue Man Group is currently touring the US and showing in Boston, New York, Las Vegas, Chicago, Orlando, Berlin, Tokyo, and on board the Norwegian Cruise Line. Check their website for more details but this is one show you should go back to again, and again. And don’t even think about missing it!

Museum of Bad Art (MOBA), (BOSTON, MA, USA)

Posted: March 31, 2012 Filed under: Art, Interviews, Tourist Attractions, Travel | Tags: America, art, Bad, Boston, Gallery, Louise Sacco, Massachusetts, Mike Frank, museum Leave a commentADDRESSES:

Basement of Dedham Community Theatre

580 High Street

Dedham MA 02026 (map)

Basement of Somerville Theatre

55 Davis Square

Somerville MA 02144 (map)

BATV

46 Tappan St., Top Floor

Brookline MA 02445 (map)

PHONE: 1.781.444.6757

WEBSITE: www.museumofbadart.org

Free entry. The Dedham and Somerville branches are open whenever films are showing at the theatres, and the Brookline branch is open during BATV opening times.

MY SHORT STORY:

- Instead of being offensively terrible, the art displayed in the Museum of Bad Art (MOBA) is endearingly ‘too bad to be ignored.’

- The museum is a non-profit organisation that is free to the public. It started when an arts and antique dealer called Scott Wilson found a painting now known as ‘Lucy in the Sky with Flowers’ in a pile of rubbish on the roadside in 1993. His friend Jerry Reilly liked it so much that he insisted on keeping it. The two guys, with a little help from three other friends and family members, set up MOBA in Jerry’s basement. They moved to the basement of Dedham Community Theatre the following year, and two branches in Brookline and Somerville opened a few years ago.

- I had a chance to meet Mike Frank, MOBA’s current Curator, and Louise Sacco, one of the museum’s original founders and current Executive Director. They told me that sincerity and originality are factors they look for in the paintings they choose to display, not unlike the criteria used to select works in traditional galleries. The works have to have started off as a serious attempt that went wrong for whatever reason. They like all paintings on display.

- Mike and Louise insist that they are not out to offend anyone, but rather to mock the pretentious artspeak used by art critics.

- I personally really love the paintings, as they are all insane but still pretty and quirky. You can’t help but wonder just what the artists were thinking when they made these works. It’s really interesting finding out the stories behind them.

- MOBA is a magical and cheerful place for second chances, and breathes new life into abandoned pieces with lighthearted humour. I love it!

MY FULL STORY: As some of you may have read in my Northern Art Prize and other articles, I have been getting quite angry about what Art seems to have come to become these days. It’s as though anyone can create any piece of crap and as long as it is prettily framed it can sit quite comfortably on a stately gallery wall.

Clockwise from left: 'Bone-Juggling Dog in a Hula Skirt' by Mari Newman; 'He was a Friend of Mine' by Jack Owen; 'Jerez the Clown' by Higgins. Photo by Gwen Pew, Apr 2012.

So is there such thing as ‘bad art’? My answer lies in three wonderfully underground locations around Boston, Massachusetts – the tongue-in-cheekily named Museum of Bad Art (MOBA). But instead of being disgusted by the works on display, I was actually very attracted to them when I visited their Brookline and Somerville branches, perhaps because they aren’t pretentious at all. There is actually something very endearing and quirky about each painting.

Take Mari Newman’s ‘Bone-Juggling dog in a Hula Skirt,’ one of the museum’s resident heroes children usually love. It is an explosion of nonsensical madness on canvas, but you can’t help loving the dog’s playful expression and wonder just what the artist was thinking when she created this.

As it turns out, in case you were wondering the same thing, Newman had originally wanted to just paint a wiener dog standing upright. When the attempt failed however, she decided to add random things to it, including a hula skirt (inspired by girls in a magazine) and dog bones being juggled (inspired by a visit to the pet store).

Gisela Keller’s ‘Elián Gonález’s Grandmothers’ is another favourite of mine. The garden in the painting is stunningly painted, as are the two ladies strolling in it – and yet something doesn’t quite fit. For one thing, they seem to be slightly too small for their surroundings. For another, they have no shadows, so they are literally just floating in the landscape. Still, it doesn’t detract from the fact that it’s beautiful on a very basic level.

‘The way that we select our works is actually very similar to traditional galleries,’ explained Louise Sacco, one of the original founders and now the Executive Founders of MOBA. ‘We still look for originality, sincerity… we have very strict criteria.’

Mike Frank, MOBA’s Curator, agrees sincerity is an important factor and that they have to feel drawn to the works.

Mike Frank, MOBA's Curator, chosen apparently because he was the museum's most generous donor - and he owns a tux. Photo by Gwen Pew, Apr 2012.

‘We like all of them. If we don’t then why would we put them on display?’ asked Mike.

More a labour of love than anything else, MOBA is a non-profit organisation that runs purely on donations, book sales and the generosity of bad art lovers and supporters.

The variety of art on show all have their own stories and origins. Some are donated by the artists directly, but most are ‘rescued,’ as Louise likes to call it, from thrift shops or rubbish dumps.

So what counts as bad art?

‘I think the terms ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art are problematic,’ Mike said. ‘The works on display at traditional galleries are important. The ones you get here are just a bit off, for one reason or another. You won’t find them anywhere else.’

‘They have to have started off as a serious attempt,’ Louise agreed. ‘But went wrong either because it was a bad concept in the first place or that it was just poorly executed.’

The story of MOBA began in 1993 when an arts and antiques dealer called Scott Wilson found a painting – now known affectionately as ‘Lucy in the Sky with Flowers’ – in a pile of rubbish on the roadside. He had originally only wanted the frame to sell as antique, but when he showed it to his friend Jerry Reilly, Jerry insisted on keeping the whole thing.

And so ‘Lucy’ was hung along with other acquired works in Jerry’s basement for a year, managed by Scott, Jerry, Jerry’s wife Marie Jackson, sister Louise Sacco, and their late photographer friend Tom Stankowicz. By 1994 the makeshift gallery had acquired a fair bit of fame and media coverage, and they moved to a somewhat more formal home – the basement of the Dedham Community Theatre, where it still stands now.

Their Somerville and Brookline galleries opened a few years ago, and the three galleries are now popular local attractions.

Louise Sacco, one of the Founding Fives of MOBA and current Executive Director. Photo by Gwen Pew, Apr 2012.

Louise and Mike are both careful to stress that they are not out to offend the artists or their art – but to celebrate them. In all the years that they have been involved with MOBA, there was only one case of complaint. Most other artists are delighted when they find that their works are on display there. After all, who doesn’t want their works to be displayed in public?

‘We don’t accept works by students or children – we have made it a thing that all art by them are good art because we don’t want to discourage or make fun of anybody. If there’s anything we want to mock, it’s the high brow, pretentious artspeak used by critics,’ Louise said. ‘And they’d just have to get over that!’

However, not everyone ‘gets’ the idea behind MOBA and what it represents, as Andrea Kalsow tells me. Andrea works at Brookline Access Television, the office lobby of which is the location of MOBA Brookline. She personally loves the works, but does sometimes see visitors who just obviously have no clue what the artworks are about.

‘This guy took his friends here once and he was so enthusiastic in trying to explain why they are “bad art,” but his friends just didn’t get it at all!’

To me, these works are examples of poor communication that still look pretty. Art is about expression, but there are times when they just don’t work out the way that the artist had intended. And there’s nothing wrong with that, as long as they recognise it and don’t try to pass it off as important art. In most cases I can still see the intention or idea behind the works, which I think is the most important part.

I love the fact that MOBA has been set up as a forum to display art that would have been abandoned otherwise. It is a magical and cheerful place for second chances, and breathes new life into brave but thwarted attempts of creativity with lighthearted humour.

And the best part? Unlike most galleries and museums in America, MOBA is absolutely free and accessible to all.

I was thoroughly amused and delighted by my visits. Three cheers for the low brow, wicked bad art!

Sam Wills (aka The Boy With Tape On His Face), Comic (LONDON, UK)

Posted: March 15, 2012 Filed under: Comedy, Interviews | Tags: comedy, comic, interview, New Zealand, Sam Wills, The Boy With Tape On His Face Leave a comment

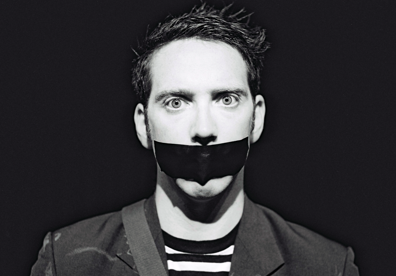

Sam Wills, aka The Boy With Tape On His Face, Comic. Photo from http://www.theboywithtapeonhisface.com.

When looking for audience participation, how do you pick your volunteers?

Apart from ‘Tape Face’ what other shows (comedy or otherwise) have you taken part in?

Do you constantly add new elements to the show? Where do you get your inspirations?

You’ll be touring everywhere from Dubai to South Africa – how did you first break into the international stage?

What is the most difficult thing about being a mime comedian?

Any words of wisdom for all the budding comedians out there?

* ** *** ** *

Click here to read my review of Sam’s show at Stanley and Audrey Burton Theatre, Leeds!